Game hacking on Linux

I always liked to play computer games. They are complex pieces of software. In the past most games had cheat codes, but nowadays it’s less common. As an engineer I like to see how things work, so let’s reverse engineer an open-source game on Linux called Xonotic and create a small cheat to have infinite health and ammo.

How are game hacks made

To completely understand how cheats are made, some knowledge about how programs and memory work is valuable. Most common operating systems allow processes to read and write memory on other processes, which can be used to cheat in games. Values such as health are often stored in dynamically allocated memory. This means that when the game is restarted, the memory address that keeps the health will change. However, there is always some static base address that points to the health address, we just have to follow the pointers using static offsets.

Cheat Engine

The most popular tool to hack games is Cheat Engine. It is an open-source memory scanner and debugger. As most games on PC are for Windows, that is the primary focus of the software. On Linux it uses a client-server architecture so we must download the Linux server and also the Windows client, which must be executed on Wine.

Searching the health

The first step is to start the cheat engine server using sudo and then the client. Afterwards connect to the server on File > Open Process > Network > Connect and select the game process.

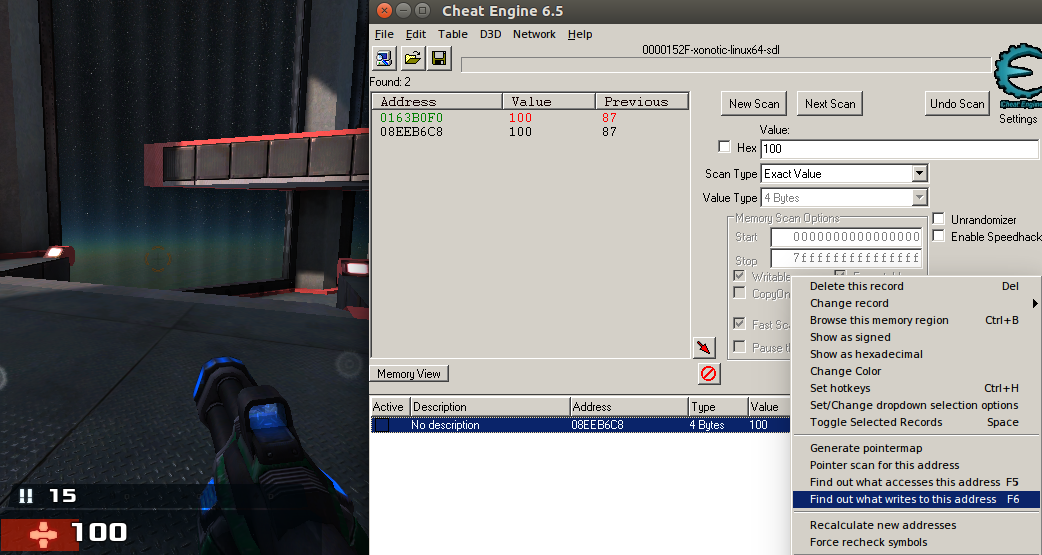

Now we can search for the health. Start with 100, scan, take a bit of damage, scan again until we have few addresses. Green addresses are static and finding them so soon usually means that it is not the address we want. Let’s try the other address and “Find out what writes to this address”.

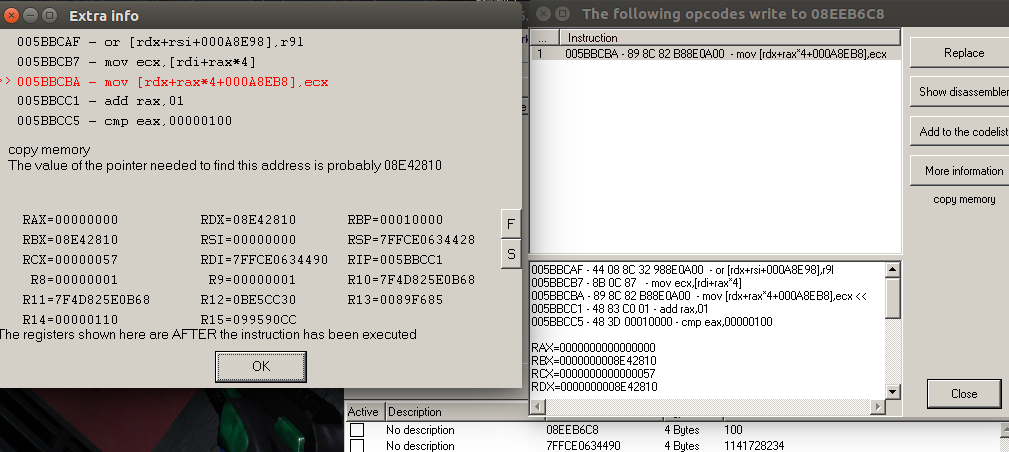

A bit of assembly knowledge is useful. We can see that the mov instruction copies the value from the ecx register to the address we found. On the line above, the ecx value is copied from the rdi register, which contains the address 0x7FFCE0634490. As rax is 0, the addition and multiplication do nothing.

Let’s add the address we found and “Find out what accesses to this address” and we can see that many instructions access this address. Since the health is being copied from here, we will have to search all of them until we find some register with the value 100 (decimal), which will be 0x64 (hexadecimal). Luckily, I didn’t have to search a lot and then I clicked the “Show disassembler” to open the Memory viewer. In here we can place some breakpoints and debug the program.

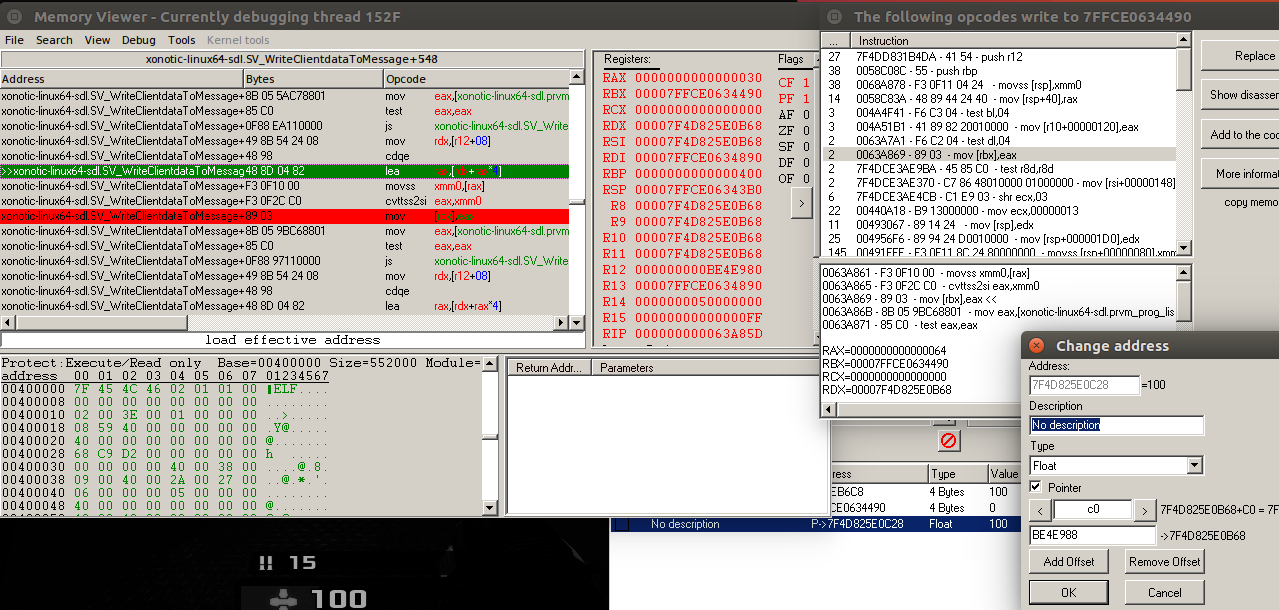

This is very insightful! The cvttss2si instruction is used to convert floats to integers. Going back a little we find the lea instruction which is copying the health from the address in edx + rax * 4. With the multiplication we get our first offset, 0x30 * 0x4 = 0xC0. The rdx is set based on rd12 + 08, which is 0xBE4E988. We can verify this by adding the pointer and offset to the list of addresses and by setting the type to float.

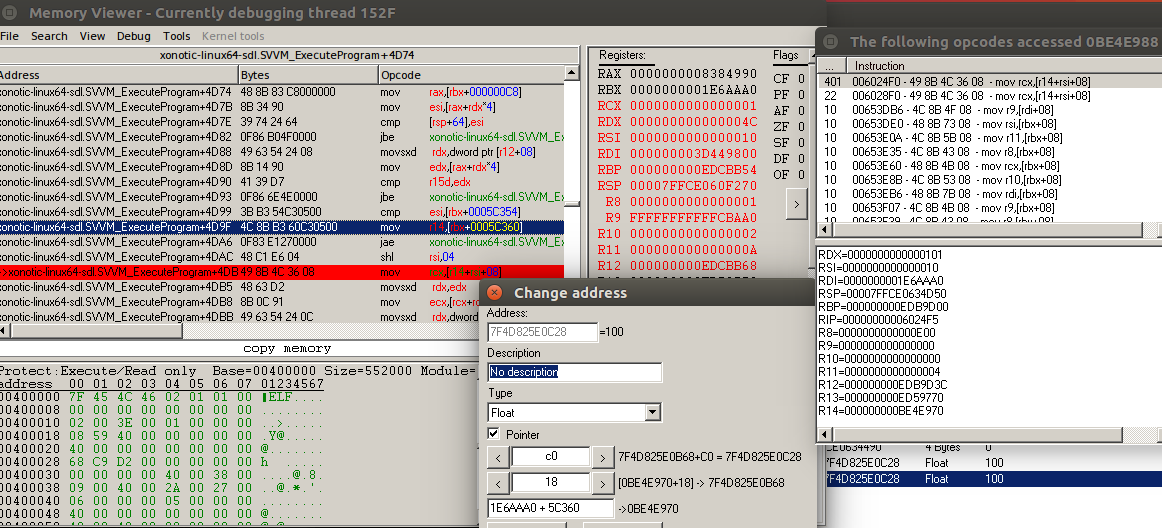

Now we need to find out what accesses to this pointer. These steps of finding the base address may involve trial and error. Let’s pick the first instruction and we know from the mov instruction that the offset is rsi + 08, which equals 0x18. The r14 register has an address and by looking at an instruction above, it is obtained through rbx + 0x5C360 and rbx is 0x1E6AAA0. As this address is static, it is our base address to get to the health, by applying the correct offsets.

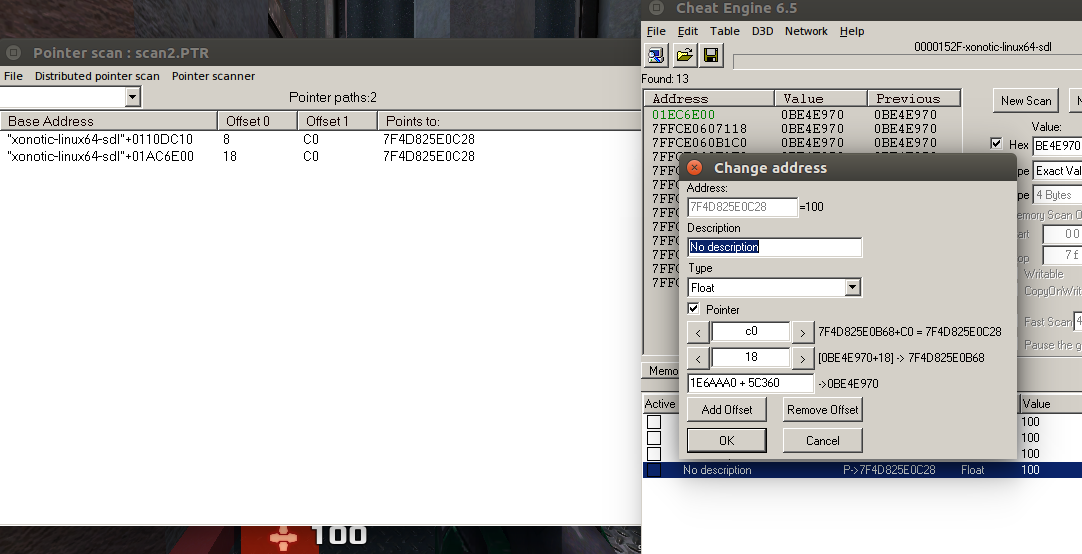

Pointer scan

An alternative to this backtracking is when we find the real health address, we do a pointer scan. We see 2 different pointer paths, to pick the right one we can restart the game and see which still points to the health. The static base address with the offset 0x18 is the same as the one previously found but is getting calculated using the “xonotic-linux64-sdl” module address.

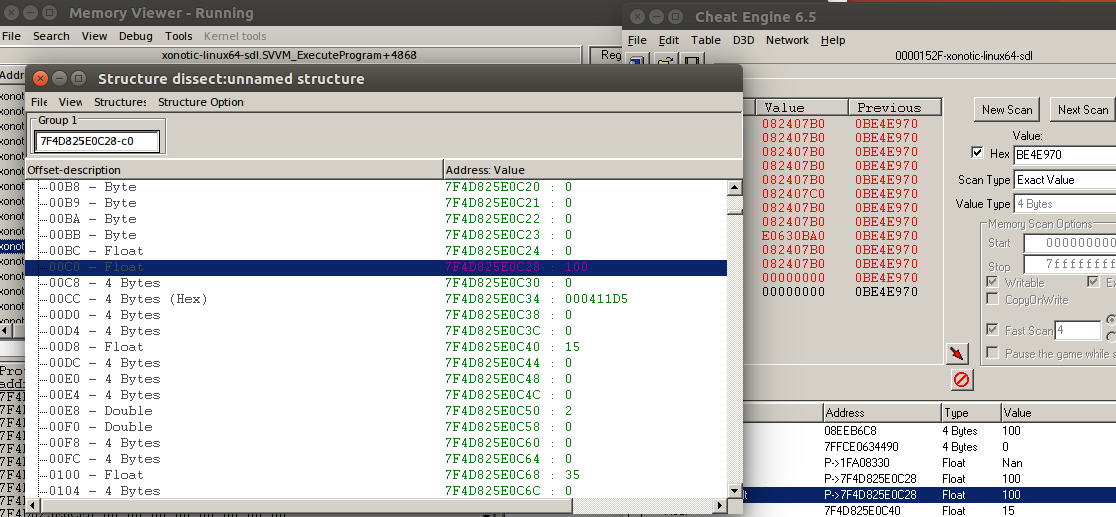

Dissect data structures

To find the ammo, I took a quick shortcut. Usually games store the player data in a struct or a class and as such, it’s highly likely that the health and ammo are in close memory proximity. By using the Dissect data structures feature from the Memory Viewer > Tools > Dissect data/structures > Structures > Define new structure we find that the ammo is just a few bytes away from the health, with the value 15.

Coding

To read and write memory from other processes we need to call APIs that depend on the operating system. For Linux we can use ptrace or process_vm_readv and process_vm_writev. On Windows, the functions ReadProcessMemory and WriteProcessMemory are available. Alternatively, a module (.so/.dll) can be injected into the game to avoid using these APIs and enable direct memory access. The best language for these low level things is C or C++.

1 | bool read_addr(pid_t pid, unsigned long addr, void *buffer, size_t size) { |

Using system calls is an expensive operation. As such, it is better to create a struct to hold the player information and read one bigger chunk of memory at once, than many small chunks. As we are getting to the dynamic player structure address by reading pointers through a static base address and offsets, the cheat will always work when the game is restarted, however these offsets may change when the game is updated. There are alternatives to get to the dynamic address that may resist game updates which are based on signature/AOB(array of bytes) scans.

1 |

|

Cheats are usually running in some infinite loop until they detect the game is not available. Sleep commands avoid hitting unnecessary 100% CPU usage. Global keyboard input detection to toggle features is helpful (code is OS dependent). An alternative to writing the health constantly, would be to patch the code that decreases it, like replacing a mov with nop instructions, which could be done by writing the correct bytes at the correct address.

1 | void open_game(Game *game) { |

Keep in mind that this hack works for single player only. Server side software should keep their own health value for each player and as such we can’t change it, any local change will be visual only.

Modding and game development

With reverse engineering it is possible to develop complex mods, adding new features to games. For example, San Andreas Multiplayer mod was created by identifying memory structures, intercepting engine functions and building a client/server network layer to synchronize state. Richard Burns Rally is kept alive by an active modding community, which reverse engineered the game to understand its file formats to create new tracks and cars and hooked the game engine to improve physics and add new functionalities.

Games that are fun and support modding or plugins tend to have a good longevity, as players can build new content. Some examples include Assetto Corsa, rFactor 2, Counter-Strike, L4D2, Quake, Doom 3 and many more. Modelling of 3D tracks/maps is usually done in game-specific tools like Bob’s Track Editor, 3DSimED3, ksEditor, Hammer Editor, GtkRadiant, with some allowing configuration of bot AI. Depending on the game, it is also possible to create assets in modelling software like Blender, which can then be imported to the game editor (or even directly to the game supported format, if a Blender plugin exists). I’ve seen an impressive video of using photogrammetry software to generate an Assetto Corsa map based on a real city, which if fully done manually would be significantly more time consuming.

Nowadays, modern game engines like Unreal Engine or the open-source Godot make it easier to develop advanced 3D games, so building from scratch can be an alternative for modding. There is also a healthy collection of open-source FPS and racing games:

- Xonotic

- Red Eclipse

- Unvanquished

- Assault Cube

- Speed Dreams

- Trigger Rally

- Rigs of Rods

- SuperTuxKart

Developing 2D games is often simpler but they are less immersive, even when using techniques like raycasting and sprite scaling to achieve a 3D illusion. If you are looking for some open-source 2.5D games, check the following:

Closing thoughts

Reverse engineering is hard. I admire the researchers who have to analyze software/malware in similar ways. Making complex cheats is also extremely time consuming. For example, we can draw enemies through walls or even automatically aim and shoot against them by reading their coordinates and applying some game/engine dependent math, but a lot of study is required.

The full source code is available on GitHub and was tested on Ubuntu 16.04 and Xonotic v0.8.2.